This is based off a talk I gave on improving communications.

There is a lot of communication right now

With everyone working remotely, the importance of communication has increased. We’re communicating more often without meeting, and making your message clear when everyone is deluged with correspondance is the only way to have impact in your organization.

To succeed in any organization, you need to be able to tell your story. Whether it’s a status update, an RFC, or an escal question, you need to be able to quickly tell people the state of the world. It’s how you’re going to convince other people to take action or to answer their questions.

People need structure to their stories. In order to follow a story, either written or spoken, people need to understand how all the given information is related. When you present your story, your audience will look for connections between things you’re saying, such as: there must be a reason for that statement; or, this is probably an example of the previous point.

This structuring can be a conscious or unconscious process by your audience. People automatically look for structure.

Without structure to your communication, your message can get lost

Communicating information, whether on a Zoom call or in Slack, well it’s hard. If you don’t present a clearly structured story, your audience will look for their own structure, which can lead to problems.

Your audience could misunderstand your structure and be unable to understand your story. Because of that, they might lose attention, or they may draw false conclusions. Even if your audience understands your story, without structure they’ll have to work hard to do so.

If they’re working hard early, they’ll have less attention later on, or stop reading and listening to you all together.

To have your audience fully grasp what you are telling them, you need to structure your story as clearly as possible. This requires you to have a clear view on your own story structure.

What’s an effective way to structure communication?

Start your storytelling with a simple structure that works. If you need to convince a analytical audience such as your fellow engineers, turn to Barbara Minto and her Pyramid principle.

She has spent decades teaching her pyramid principle. Her framework makes your arguments easy to understand and much more convincing.

I’ll introduce each element and then we will discuss some examples to make it more concrete.

Start by outlining the S - the situation.

The Situation is the starting point of your story. It is important that your audience can easily understand your story and recognize what you are telling them. This introduces them to your topic and how it relates to their world.

The Situation is made up of recognizable and mostly agreed-on points. They describe the state of the world and the topic of your work.

Of course, this is not a story yet. If you only describe a situation as it is, there’s no reason to act.

For example, let’s say you get an alert that an API is taking 500ms to respond. if I tell any of you, “An API is taking 500ms to respond”, without any context, there is no motivation to act. 500ms could be good or bad.

Next outline the C - the Complication.

This is the reason that you’re asking people’s attention for your story.

What has changed that’s making things harder? What threats do we face if the Situation carries on as it is now? What opportunities do we miss?

Explaining this in your Complication will give your story its urgency. Also part of the Complication is: what practical hurdles do we need to overcome to prevent those threats or to realize those opportunities?

With the previous example with the API alert, adding the complication might sound like, “An API is taking 500ms to respond, it normally responds in 50ms.”

If you sharply define the Complication, the Question follows naturally.

It asks how the issues of your Complication can be overcome, so that we can either stop the negative effects or seize an opportunity.

When communicating your story, a commonly agreed on SCQ makes sure that the audience understands what you want to do in your Answer, and also why this is relevant.

The question also allows your user to take a breath. Many times the Situation and Complication can be quite long. Phrasing out the question simply reminds the user, after all of the explanation, why they are here.

Using our previous example, we might add a question such, “An API is taking 500ms to respond, it normally responds in 50ms. Why is the API so much slower?”

The A provides the Answer.

It explains what we should do and how we can do it. Your Answer should be explicit in how it will solve the Complication that has been raised.

A simple SCQA for our alert situation:

An API is taking 500ms to respond It normally responds in 50ms. Why is the API so much slower? We are under 10x the normal load. We should scale up the cluster to compensate.

Breaking down the Answer

So that’s the basic structure. Now we’re going to focus on the A - the Answer. It seems to me that most folks have a good grasp on the S & C in their writings. The Q naturally falls out of that. But the A sometimes needs more structure to be effective.

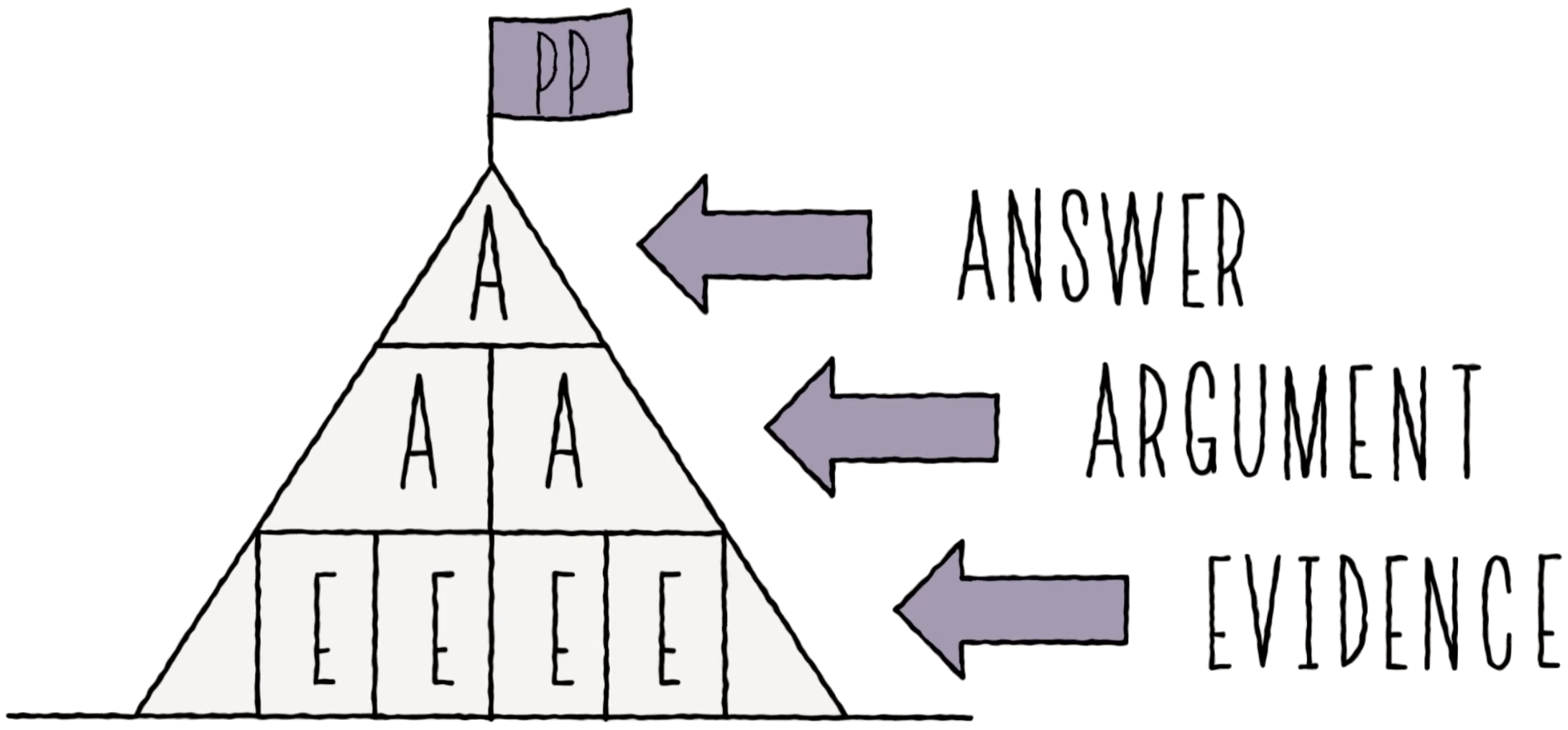

Arguments & Evidence

Once you have an answer, you can spend your time offering arguments and evidence for your answer.

And it’s going to make your arguments better. The pyramid makes your answer the focal point of the conversation. This is appealing to analytical folks who have a solutions mindset.

The pyramid creates a logical structure. Each level of the pyramid supports the level above it. Evidence supports each argument, and the arguments come together to support the answer. If they don’t, you’ll need to find better arguments.

For our alert example, you could provide evidence of the response time over the past 30 days, the db load being normal, no long-running tasks in flight, and the traffic from a certain customer being elevated.

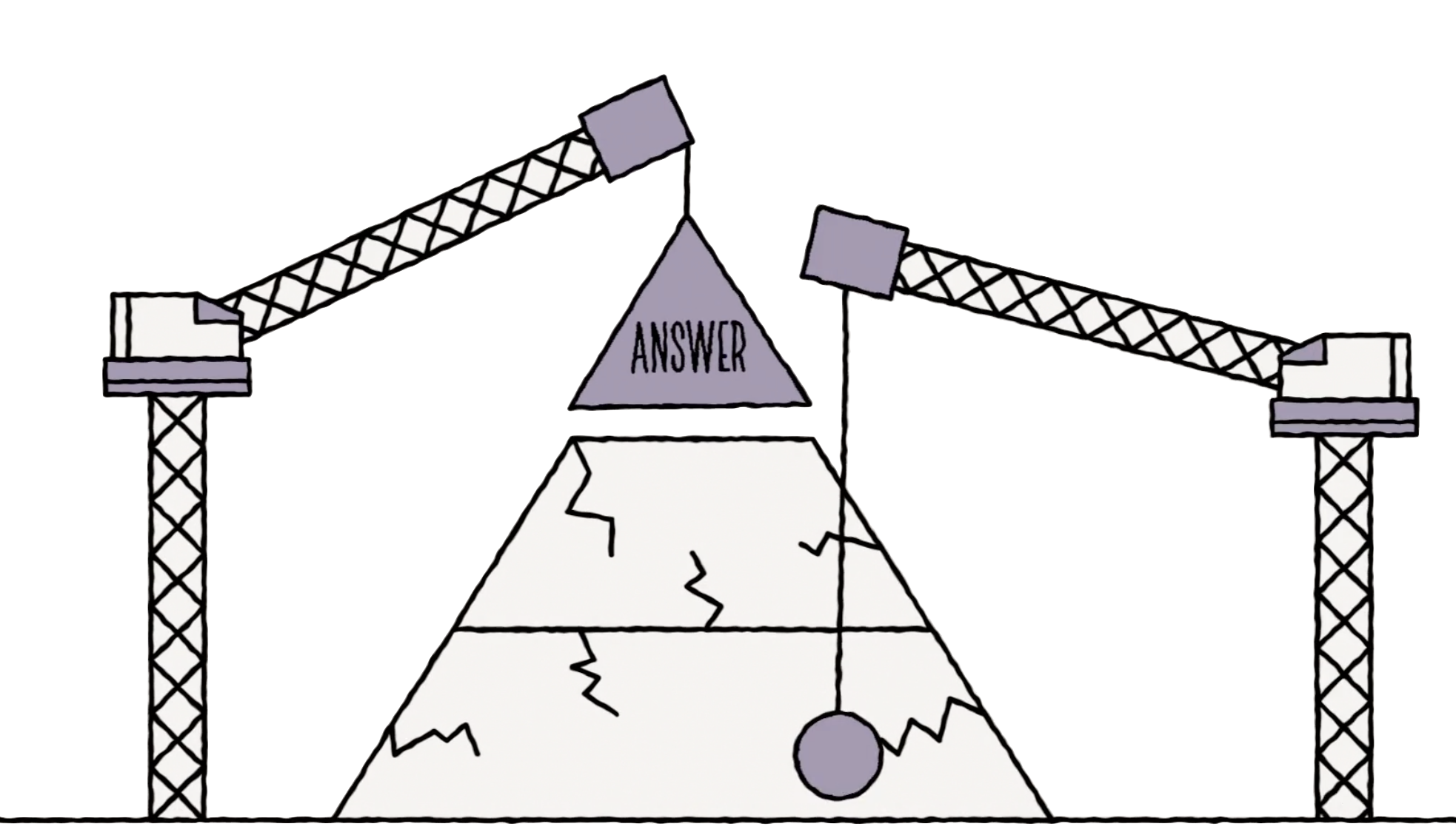

Paring down your Answer

The Pyramid requires you to pare out all the unnecessary information. Many presentations, status updates, and RFCs contain a lot of information to show that you did a lot of work. In the Pyramid, if your evidence or arguments don’t directly support your answer, take it out.

For our alert adventure, let’s say you did hours of work researching technologies such as Consul, Envoy, and Docker. Some people might put what they learned about these systems in their story to show they did a lot of research, but it doesn’t serve your answer, so take it out.

Think of your Audience

If your audience loves analysis, logic, and reason, tell stories this way.

How much do I like SCQA? I structured this post using it.